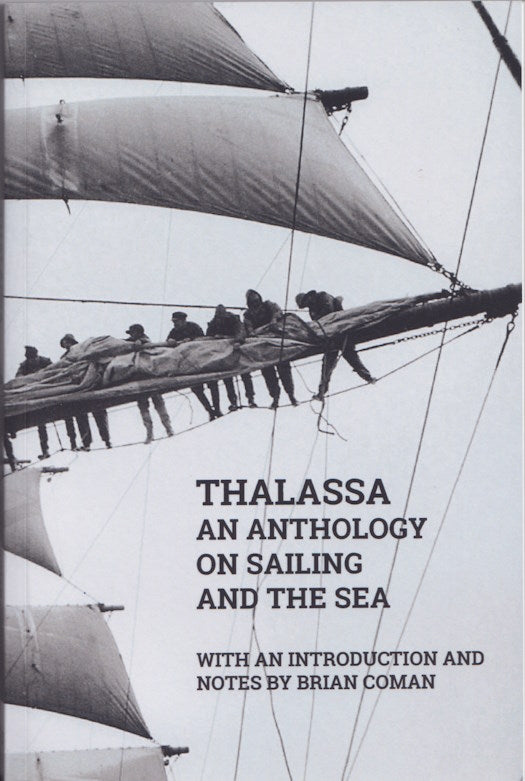

Thalassa : An Anthology on Sailing and the Sea edited by Brian Coman

Thalassa : An Anthology on Sailing and the Sea edited by Brian Coman

Couldn't load pickup availability

Thalassa : An Anthology on Sailing and the Sea edited by Brian Coman

Paperback, 202 pages, $29.95

ISBN 9781923224049

Published in 2024

From the Introduction

By its very nature, an anthology is a very personal affair. It is determined entirely by the tastes of the compiler and by the breadth of his or her reading. This is especially the case when the topic is a very broad one, as is mine. There are, no doubt, many hundreds, if not thousands, of books and essays on the sea and on sailing, and my selection represents only a tiny fraction of the material available. I make no apology for this. It is simply the result of the brevity of a single human life and, in my case, of coming to an interest in the subject matter late in life. Not until I was sixty-five years old did I first board a sailing vessel and experience that highly specific sensation of gliding over water with only the sounds of lapping waves and the hum of keel and rigging.

Again, there is always a danger involved in selecting pieces for an anthology. The selector assumes that particular works or extracts of works will move the reader just as it moved him or her. But, of course, literary tastes vary—“in matters of taste”, goes the old maxim, “there can be no disputes”. One could overcome the problem by sticking to well-known and much-loved classics, whose popularity has stood the test of time. But then, where’s the point of producing yet another collection similar to the last? I have tried to steer a middle course in this matter, dispersing little-known authors amongst old favourites. This particular arrangement has certain advantages. The reader, coming across some obscure (to him or her) writer rubbing shoulders with an old favourite, might be pleasantly surprised to find just how well this new intruder measures up. There again, reading an anthology ought to be a voyage of discovery, opening new vistas.

In choosing this arrangement, I had a particular model in mind. As a young schoolboy, I was introduced to the various volumes of The Victorian School Reader. Each Reader was an anthology of prose and poetry where Henry Kendall might sit next to Shakespeare, or Henry Lawson to Charles Lamb. The effect was marvellous. I owe a great debt of gratitude to the compilers of those Readers, for they stimulated in me an interest in literature which was to be a source of inestimable pleasure over the ensuing decades. This present volume could never hope to match the achievements of those early Readers, but in attempting to emulate their particular approach, I hope that I might gain, for authors whose works deserve a wider audience, at least a few new admirers.

The reader of this collection will quickly note that I have limited myself to older accounts of sailing and of the sea—few of the extracts are later than the 1950s. This was a deliberate choice. There have been some epic sailing adventures in more modern times, but I have omitted them in favour of an era lacking satellite tracking and other modern navigation guides, radio communication, and sophisticated sea rescue methods. There is something in that mix of real danger and human determination which gives the older accounts a sharper edge. I have also omitted accounts of racing yachts though there are many fine accounts available. This again, reflects my own interests. I have not a competitive bone in my body. Mark Twain once quipped that it is “difference of opinion that makes horse-races”. I feel the same about yacht racing.

My limited purpose in making this collection was to gather together some of those accounts which have moved me by their eloquence in describing the business of sailing and the moods and phenomena of the sea. Not all of my extracts are written by sailors; Freya Stark, for instance, was not a sailor, but her ability to paint, in word-pictures, the moods of the sea and the characteristics of sailing vessels, is unparalleled. Some of my chosen authors are little-known. H.C. Barkley wrote a couple of little-known works for young people but his description of a wild storm and of a ship-wreck is superb. Likewise, the Irish author, Maurice O’Sullivan, is little known today, but his Twenty Years A-Growing was once considered a classic. The collection includes the work of some sadly neglected Australian writers. Here, I have deviated a little from my stated purpose by including an account of a river journey by paddleboat, but the spirit of a sea adventure is there.

In my selection, I have exhibited an unashamed bias towards accounts dealing with the ancient world. Like my sailing and boat-building, I came to Homer at a late age, and it was a revelation. The Odyssey and Iliad contain some of the most beautiful, short descriptions of the sea and its creatures that have ever been recorded. Who has not heard of “the wine-dark sea”; who has not been moved by that lovely description, “down the shore of the sounding sea”? I sometimes think that all Western literature is, in a sense, merely footnotes to Homer, for in Homer is the seedbed of all human experience. For this and for other reasons mentioned above, my chosen extracts follow no strict chronological order. In sailing, the old and the new are always companionable, for the experience is unaltered.

But, more than anything else, the experience of sailing alone on the vast expanse of the ocean or walking alone along the shore of that “sounding sea” engenders the activity of reflection and of human imagination. “Life”, Plotinus said, “is the flight of the alone to the alone”. True enough: when the winds are strong, the sailor must devote all of his or her attention to the task, but in placid weather, the gentle lap of waves, the gurgling wake, the caress of soft airs and the immensity of the surrounding waters, brings on that pensive mood of personal reflection. I have tried, in making my selections, to include such experiences. This reflective mood is no better exemplified than in the writings of Hilaire Belloc. Many readers will be surprised to see him represented here, but he was more than just a fine sailor; he had a rare ability to represent, in the written word, that sort of deep longing that so often accompanies an experience of beauty or tranquillity. C.S. Lewis once described it as “an unsatisfied desire which is itself more desirable than any other satisfaction”. And so, coming into port, or dropping anchor, has a much deeper significance for Belloc and the spiritual quest is never far away. This, too, will explain my inclusion of Tennyson’s Crossing the Bar and an extract from Matthew Arnold’s Dover Beach.

At the other extreme, the men sailing on the large merchantmen had that experience of living in close contact with their comrades—working together, sleeping in the same cramped quarters and, in the little leisure time available to them, relaxing in the same forecastle. Here, too, were men from every corner of the globe, from every conceivable background and holding diverse philosophies and religious beliefs. Perhaps no-one has better explored the group psychology attending this situation than Joseph Conrad in his novels.

No-one knows when humans first took to sailing in boats. Perhaps it was the ancient Egyptians or Phoenicians. Certainly, by Homer’s time it was one of the main means of commerce in the Mediterranean. Commercial sailing reached its zenith in the age of the great clippers and then declined as the age of steam overtook it. The steamers, in turn, gave way to oil power. Today, large sailing ships are, for the most part, museum pieces, sailing for the tourist trade. The more romantically inclined among my readers will, like me, see this as a sort of regression, and they will then understand why I have included John Masefield’s Cargoes. But the age of sail is not dead. Small sailing boats are still very popular, kept alive in large measure by the sport of competitive sailing. Even where I live, in north-central Victoria, we have a sailing club and an inland lake to enjoy the sport. Each year, a cohort of young boys and girls is introduced to sailing at our club. I hope that they might, one day, come to love the sheer enjoyment of sailing, for its own sake and experience, as my chosen authors have experienced, that special sense of unity with a vessel that only sailing can give. For a boat under sail is almost a living thing, as many of my chosen extracts seek to demonstrate.

My first sailing boat, a Hartley 16, was called The Governor. The next and larger boat was, understandably, called The Governor General. Perhaps, before I die, I might justifiably call my last boat The Governed, but I doubt it. No matter! When these ageing limbs can no longer haul in the main sheet or hold the tiller in a hard wind, I will have my books. With these, I can sit in my chair and sail the world. It is my hope that the reader of this collection can do likewise.

Finally, I must acknowledge my debt to Maurice Nestor, formerly of La Trobe University, who acquainted me with several excellent books on sailing and the sea. Another colleague, Dorothy Avery, gave me access to her late husband’s excellent library of sea-faring books. I thank them both. The first edition of this book was expertly copy-edited by Jessica Milroy and any layout errors in this edition are the responsibility of the author.